Happy New Year! I’m happy to be writing this newsletter again, and I’ve determined that it’ll come to you monthly as a reflection on what I’ve read. At the beginning of the month, I’ll send along some short book reviews, and sometimes one longer review, or even a guest review or interview with an author. (My main guest will be my dear friend, art scholar, and fellow author Elise Herrala, with whom I’ve been in a 15-year-long conversation/text thread about books).

It’s sad to see venues like Bookforum and Astra Magazine closing and the landscape for book reviewing growing ever bleaker. Of course a newsletter could never do what an editorial institution does, but many of us who care about books are left to do our little newsletters. So, for whatever it’s worth, I’m doing mine.

In 2022 I read a lot. I’m sharing some of my favorites below, as well as some of my disappointments (in reading, not in life; that’s another newsletter).

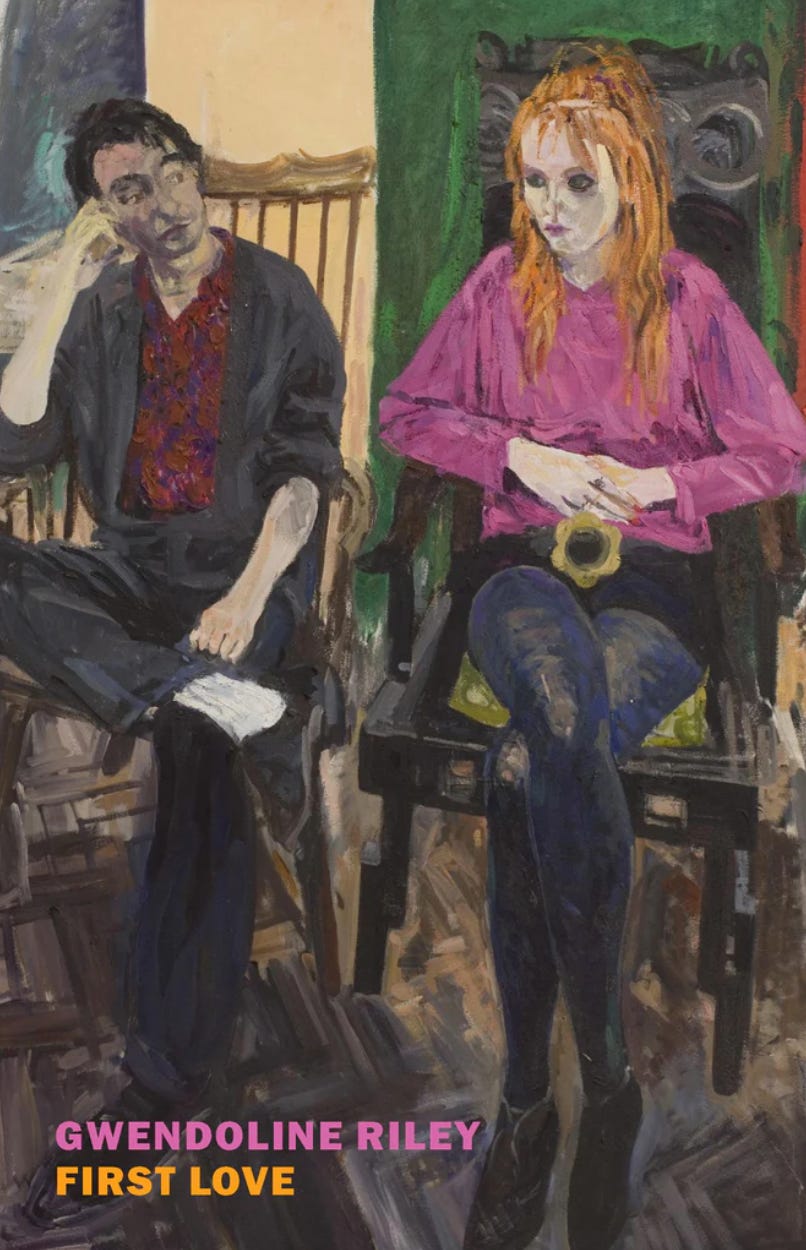

First Love by Gwendoline Riley, published by New York Review Books. As novels go, this was my favorite of the year. Sharp and sad as soured milk. Grotesque, mordantly funny, with a deeply dejected narrator and one of the best depictions of an abusive relationship I’ve ever read. There’s also death, drinking, frustrated ambition. Odd to say I found this highly relatable? Now working my way through the rest of Riley’s books (currently: My Phantoms).

Last year I read and loved Lina Wolff’s The Polyglot Lovers, and this year I devoured Carnality, newly translated by Frank Perry and published by Other Press. Wolff is from Lund, Sweden and her narrator here is also a Swedish writer who travels to Madrid on a grant. There, she meets a man looking for a place to crash; he promises to tell her an insane story if she let’s him stay. The story, a nearly 100-page monologue, involves adultery, reality television, Chinese thugs, a powerful nun, and a kind of shipwreck situation. Based on those elements (adultery notwithstanding), it sounds like something I would hate, but Wolff is so deft, creative, and funny that the 350-page ride goes by quickly and I would have happily stayed longer in this cracked universe. She’s particularly good at writing gender relations and musing on vengeance and mercy.

This is an offbeat modernist novel with Kafka vibes. The prose is often direct but the story is devilishly amusing and mildly confounding. It’s a bit like magical realism without the magic, which works well for me, as I love a novel of Big Questions but can almost always do without sorcery, etc.

My twin fascinations with literary translation and Japan were fed by this marvelous collection of short essays, Fifty Sounds, published by Fitzcarraldo Editions (and Liveright in the US) and devoted to Japanese mimetic words, or ideophones, which mimic an idea. Barton, a British writer, chronicles her move to Japan and her stuttered embrace of Japanese in this memoir-in-essays, and shows how painful, exhilarating, and above all, complex the experience is: in short, she shows how much more there is to inhabiting another language than learning a new alphabet and grammar. The book engages with Wittgenstein and other philosophers and writers and is full of humor, awkwardness, self-revelation. I just returned from my first trip to Japan (!) two days ago, so I plan to revisit this one in the coming year.

This novel, If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English, published by Graywolf (and winner of the Graywolf African Fiction Prize), bears the hallmark of a debut: it feels like every beautiful sentence the writer has ever thought of has made its way into this book. (I googled her and found that she published a novel in verse before this one, but still). And there are many; her prose is beautiful. But the format of the novel is just as engaging: Naga moves back and forth between the perspectives of an Egyptian American woman in Cairo and her Egyptian lover, an unemployed cocaine addict from a small village, in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. They both think they understand the other; both are largely wrong. But the action builds and this is ultimately a gripping story about lust, power, violence, and guilt, and figuring out where and how to belong.

Others I really enjoyed:

I Used to Live Here Once: The Haunted Life of Jean Rhys by Miranda Seymour — excellent biography of a brilliant, mercurial writer; reveals a much more complicated story than the one we know, which is that she was often drunk.

Say Something Back & Time Lived, Without Its Flow by Denise Riley — haven’t shut up about this one all year. Grief in poems and philosophy.

The Days of Afrekete by Asali Solomon — a dinner party novel (my literal favorite) with echoes of Mrs. Dalloway, set in Philadelphia, featuring political corruption, college lesbians, and fraught class dynamics.

Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason — recommended by my sister from an airport. Looked silly, turned out to be one of the best books I read all year. Smart, sad, funny. Relationship fiction of the highest order. Annoys me that they still market books this smart as a kind of chick lit. A novel of this caliber by a man would be seen as high literature.

Brood by Jackie Polzin — sad, pretty, meditative novel about raising chickens in the aftermath of a miscarriage. Very white-lady fiction (I wonder why I’m more likely to call this white-lady fiction than British novels by white women), but lovely.

Several People Are Typing by Calvin Kasulke — only intelligible if, sadly, you’re obligated to live your work life on Slack, as I am. A story told through Slack messages that reveals the horrifying sameness of all office personalities and by extension a large swath of modern life. I laugh-cried through the multi-voiced audiobook in a couple hours.

And a couple books that let me down:

Groundskeeping by Lee Cole — I’m sure there are some who do it well (?) but in general I think it’s safe to say hetero male navel-gazing in 2022 is pretty cringe. Here, a working class MFA student with a Trump-supporting dad falls for a hot, more successful (exoticized) writer from the former Yugoslavia. Neither is that compelling. They have a weird relationship and unappealing sex. Appropriately, this felt like an MFA thesis project that would not end. I finished it anyway. And wondered why I liked a not-dissimilar novel, Early Work by Andrew Martin, so much more.

The Pachinko Parlor by Elisa Shua Dusapin — Dusapin wrote a simple, moody book called Winter in Sokcho, which I enjoyed last year, although I was quite surprised when it won a National Book Award. I found this one, called “nuanced and beguiling” on the jacket, to be neither. There’s more to be said about short, spare, largely plotless novels and the small but significant differences between those that work and those that don’t (if someone has said it, especially in a nuanced and beguiling way, please send me the link), but suffice it to say sometimes simple is just simple.

There are a few others I could really go off on, but I’ll close in a positive spirit. There is SO much I look forward to reading in 2023! See you next month!

Yes yes to your review of Sorrow and Bliss! I thought I was grabbing a "guilty pleasure" but the experience has made me reassess the concept of such a thing. Pleasure should never be guilty and that was such a good book. Really looking forward to reading Gwendoline Riley for the first time this year. Love the newsletter!