In addition to the ambient grief and uncertainty in the air, it has been a challenging season of disappointments and rejection for me. It's funny to respond by starting this newsletter, but I have the sense that these particular bad feelings can only be bettered by cracking open even more. More vulnerability, more willingness to be rejected or misread. Gross.

I've been thinking about the risks we take by being honest in public. I published a memoir this year, following which many people said the thing you are supposed to say, I guess, which is that it's "brave" to do so. (I think there tends to be some judgment implicit in the comment, but who am I to say what others mean). It didn't feel particularly brave. At the time of its publication, the book felt like a very curated piece of writing that shared a streamlined and controlled version of events along one plot line of my life. I had kept a lot to myself. The relationship I described sounded like a horror show, and yet I left out the worst of it. In many ways I also left out the best of my life, moments of joy and humor, especially the garden of tender new growth I've been watering every day in sobriety that I didn't want trampled by nasty Goodreads reviewers.

As the year went on, however, and we all grew pared down, worn down by hardship, my feelings changed. I shed protective layers, became more of a homebody, more muted. I knitted soft things, learned to manipulate dough and in the process became perhaps a little more doughy. I began to feel some regret about the story I'd published and fell into dark narcissist rabbit holes of obsessive thinking. Had I given away too much of myself? Pigeon-holed myself by writing about drugs? Only a few people manage to write about drugs and maintain their literary credibility and most are men. My book has pink flowers on the cover—why had I let that happen? Would I ever be taken seriously? Exhausting, pointless anxiety. And just a mental diversion, maybe, a temporary deferment of the larger question of whether we’re all going to die of Covid.

Like so many, I experienced profound alienation about the political climate this year, which made me feel the way I did as a teenager: enraged, sickened by adults' hypocrisy, hopeless. It is almost as if political disgust and turbulent self-esteem, pillars of my bewildered adolescence, still come as a pair. I have felt kind of like a teenager these past months, just one with a lot of unshirkable responsibility.

All this to say, I've struggled with legibility this year, in part because I don't always feel legible to myself. For a time I didn't recognize myself without makeup, but when I put makeup on again, I looked like I was in drag.

Each day the world is differently unrecognizable and so am I.

I’ve read three novels about alienated women in the past couple months (okay, I’ve read like six thousand novels in a row about alienated women, but these are three recent ones): The Shame by Makenna Goodman, Long Live the Post Horn! by Vigdis Hjorth, and Grown Ups by Emma Jane Unsworth. I’ve been evangelizing about Vigdis Hjorth on social media—her novels have been a deep comfort to me this year. They are serious, sometimes solemn, and also hilarious, and this one (from 2011, newly translated) is a surprising and determinedly odd story of despair and self-discovery that’s very socialist and really moves me.

The other two, both excellent, revolve around one woman’s obsession with another woman’s social media presence. The protagonists maintain the requisite self-awareness and self-loathing about their incessant refreshing of one perfect Instagram page, but they are drawn in—addicted—anyway. The Shame is unsettling and literary and funny. I’ve recommended it ceaselessly the past few months. Grown Ups is just funny, like outrageously laugh-out-loud funny. Unsworth does high chick lit like no one else. (I know that designation is sexist and has rightly fallen out of favor, but I mean it here in the most awed and respectful way, it is an art). This genuinely distracting book feels like it comes pre-adapted for the screen, it’s like if one of the breezy shows about women in publishing/media that I love to loathe (The Bold Type, Younger, e.g.) was actually good. (Incidentally, Unsworth’s previous novel, Animals, a personal favorite about two alcoholic friends in their 20s, is now a film starring Alia Shawkat).

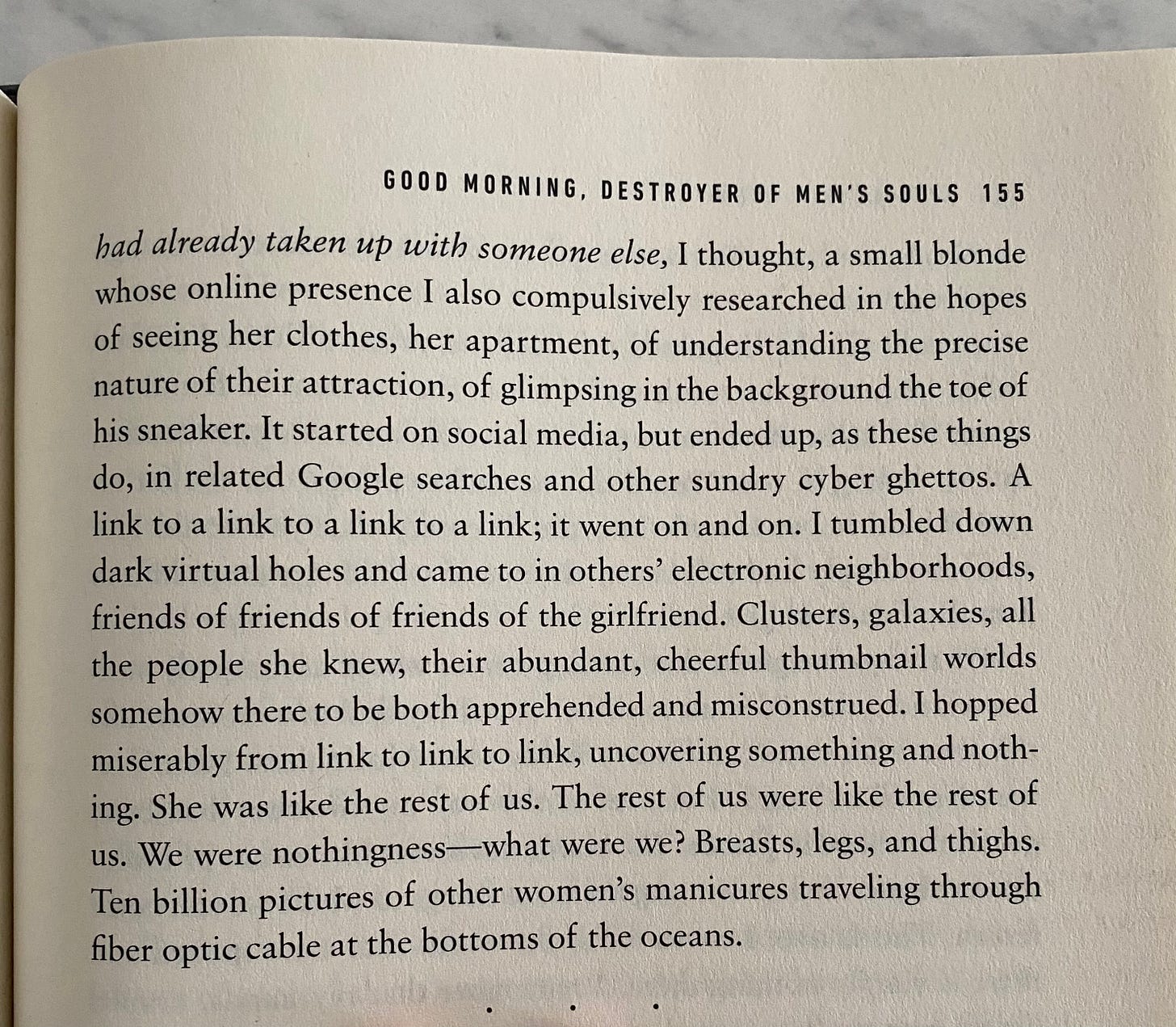

There was a very long section in a draft of my book about social media and the abyss of women’s wasted time, hours spent sizing up other women’s crop tops or crystals or toddlers or ashwagandha lattes, which was ultimately condensed into this paragraph:

Reading both The Shame and Grown Ups made me think about this tragic whooshing of manicures through fiber optic cable. I know the little pictures we share—all of the posts on all of the platforms, all of the texts—are just yearnings for human connection. But that’s even sadder still.

Anyway, I will always thrill to read novels about desperate women stalking other women, but it is also depressing, especially now for some reason. This year I marveled at those who are generationally or constitutionally better suited to social media than I am. I really am sometimes genuinely impressed by this facility (though also often annoyed) but it does bring out that wearying envy. And I don’t want to live in that place. That is one resolution: less of whatever that is in 2021.

Last week I attended a video performance my sister Leah did at the Franklin Furnace Loft in New York. The piece, called Heel on Earth, was about the time she spent working as a stripper in a pre-Giuliani New York City, but it was really about using her time in solitary lockdown to re-learn to dance, with the virtual help of a dance teacher, entirely apart from the sex work economy or the objectifying gaze of patrons.

I was so moved by the piece, which you can watch here, especially for the way it reflected the wisdom of age and time. It was a joyful reclamation of a bodily practice and a clever invitation to and refutation of a particular kind of scrutiny. The sequence of her practicing is overlaid with audio of a text she wrote, a series of memories of that time, and they are smart and sad and funny, beautifully evocative of what she calls “the calamity of being female.”

Leah’s piece made me think of the artist Janine Antoni, who also put her body at the center of her work. In her 1993 piece "Loving Care," she dipped her long dark hair in a bucket of hair dye and mopped the gallery floor with it. I had this still photo from it hanging on my bulletin board for years.

The piece was an enactment and an indictment of numerous forms of feminine labor but it was also a gesture of hostility: in performing this solitary act, Antoni also mopped viewers out of the space of the gallery. I love that. After watching my sister’s performance, I’ve dipped back into reading about Antoni’s phenomenal work and may have to write more about it. I leave you with another one of her pieces from the 1990s, “Lick and Lather,” for which the artist licked her own likeness into seven classical busts made of chocolate and washed her likeness into another seven made of soap.

All hail feminist art.

A few good things I read this week:

This Vice article about the wellness-industrial complex and how we don’t have “work on ourselves” forever (thank fucking god)

This tribute in Zachary Lipez’s newsletter to Sam Jayne, who fronted the band Lync in the 1990s (I loved them) and died this week at 46

This Johanna Fateman piece in the New Yorker about photographer Nancy Floyd’s unpretentious project of chronicling her life